The Two-Headed Worms in my Basement

Or, the Quest to Read/Write Pattern Memory in Living Organisms

“I’d love to stay longer, but I really need to get home and feed my worms.”

Statements like this have become second nature to me, and I have become well acquanted with the confused looks they elicit from people unfamiliar with my research. Over the past few years, I’ve raised several colonies of planaria in my home lab, so far including D. japonica and D. dorotocephala. As my setup has evolved, these hardy little flatworms have lived in various hideaways, including bathroom cabinets, cardboard boxes, and most recently, the belly of a grandfather clock.

In today’s entry of the Principia Fantastica, I’d like to introduce you to these amazing worms, and explain a bit about why I work with them.

Why Planaria?

Planaria are pretty darn cool as far as worms go. They are wildly regenerative, have a true brain, and even show evidence of retaining memory following regeneration of a lost brain. I plan to write more on their remarkable learning abilities in a future piece, but for today, my focus is on a different type of memory. Pattern memory.

Before we get into pattern memory, let’s first go over the basics of planarian regeneration with an example. Imagine that a planarian has encountered a rough stroke of luck out in the local pond. Maybe it got stuck between some sticks, and lost its tail while wiggling free. After tearing itself in half, both halves of the worm will regenerate new copies of what they lost. The headless fragment will mostly sit dormant while it regrows a new head, while the tailless fragment may go about its business while it regrows the missing tail. The end result is two fully functional worms. Although being split in two may sound unpleasant, it’s actually quite natural for many species of planaria. Some asexual species, D. japonica included, must rip their bodies in half to reproduce!

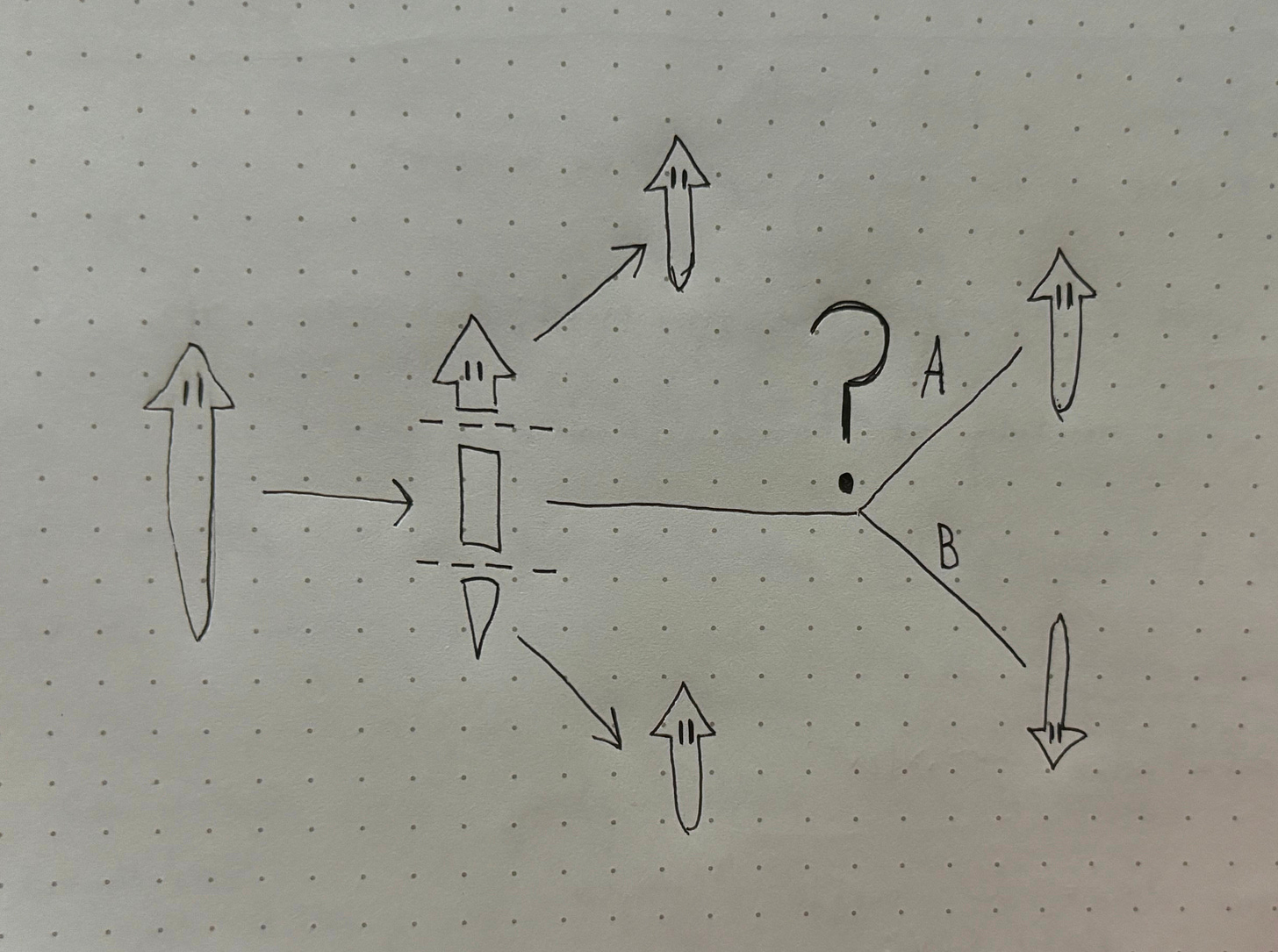

Now, let’s consider a more complex scenario. In the above situation, the worm has one wound on each of the resulting fragments, and each wound will regenerate into either a new head or tail. Now imagine that the worm is split into three pieces, resulting in one head fragment, one tail fragment, and one midsection with no head or tail. The head and tail fragments will behave as seen in our first example, but the midsection offers us a new puzzle. Without a head or a tail to orient itself, will it always regrow a head on the same side as before? A quick sketch will help us visualize the question:

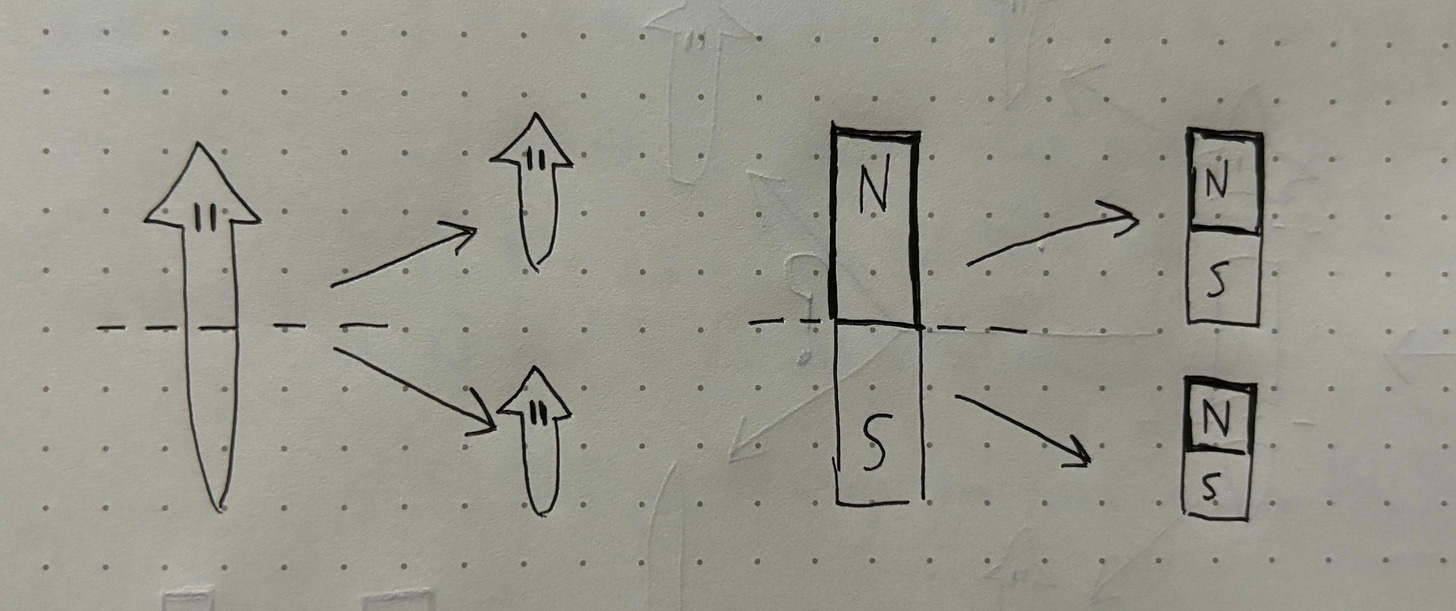

It turns out, unless we interfere in the process, Path A will always win out and the head will grow on the same side as before. In fact, the head and tail of the planaria are somewhat like bar magnets. When a bar magnet is cut in half, you end up with two complete (albeit smaller) bar magnets with the same orientation as the original. Planaria demonstrate a similar feature, in that new fragments retain the axial polarity of the original worm. Even if we cut the worm into multiple mid-sections, it will exhibit a consistent drift back towards the original shape. This original shape is what we will refer to as pattern memory.

What does memory have to do with it?

So far so good, but what does memory have to do with a regenerating worm’s shape? This is a great question, since we don’t usually think about memory in relation to biological structure. After all, we don’t talk about the shape of a human in terms of memory, so why should we treat the shape of a planarian any differently?

This is where things get interesting.

The question becomes: what do we mean by memory? Practically speaking, a memory is something that changes in a system based on past experience which influences how that system behaves in the future. For example, imagine a young child is handed an orange for the first time. The child is unlikely to know how to peel the orange, but after being shown how and getting some experience with peeling it, their behavioral response to future oranges will be different because of this past experience. We can find similar examples in computer memory, where operations carried out in the past can be saved and then drawn on in the future to enable new functions. Scientists like fancy terms, and as a field we’ve landed on the term “Engram” to refer to the physical change in a system that represents a memory gained from experience.

Now, back to the planaria and pattern memory. By our definition, in order to call morphology (the fancy science term for “shape of the body”) a type of memory, we would need to demonstrate that planarian morphology can be changed in the future as a function of past experience. This has been demonstrated by the Levin Lab at Tufts University using several different interventions that target bioelectric signals pathways in the worm. Several chemical interventions have been reported, but we will focus on one in particular that is relatively simple to implement. This method of choice is gap junction inhibition.

Bioelectric Signals: A Source of Cell Coordinate?

Gap junctions, also called electrical synapses, are little channels that connect cells and allow them to rapidly exchange electrical signals. The theory goes, these channels are how cells coordinate their shape, sort of like how the nervous system coordinates behavior using neurons and chemical synapses. Researchers at the Levin Lab demonstrated that by temporarily impeding gap junction activity early in the regeneration process, we can interfere with bioelectric signals between cells. In turn, when cells cannot effectively communicate, this leads to changes in the regenerating worm’s morphology. Over several experiments, they showed that double wound fragments with no head or tail could be made to regenerate into a two-headed phenotype that does not occur naturally. Essentially, instead of regrowing one head and one tail, when the cells couldn’t easily coordinate each wound regrew a head or a tail at random! Sometimes the result was a normal worm, sometimes not.

Consider the implications of this finding. By making a temporary modulation of a living organism’s cellular communication network, researchers were able to change a macrostructural component of the organism’s shape. Even more exciting, this didn’t require changes to the organism’s genes. If we can understand the mechanisms of cell communication and find ways to send our own signals to those cells, we could unlock a new era of regenerative medicine.

My Replication of the Two-Headed Worms

Now, how does all of this lead to my decision to begin raising my own colony of planaria? When I first encountered this work, I was completing my PhD research on human brain and behavior. As part of this training, I saw first hand the dangers of the replication crisis, in which many published papers failed to replicate when carried out by independent labs. The two-headed planaria struck me as an extremely promising foundation for a new era of regenerative medicine focused on understanding and writing signals in the body’s native language. However, before going too deep on this work, I wanted to replicate the result for myself. The protocol seemed straight forward enough, the gap-junction inhibitor was not that dangerous, and I was able to obtain the planaria with relative ease. And sure enough, over a few months and several iterations, I successfully replicated the two-headed morphology by gap junction inhibition! The pre-print of my replication is now live on OSF, and I’ll be submitting for peer-reviewed publication in the near future.

What’s Next from the Worm Lab?

With my first successful replication behind me, I have several future directions in the works. The end goal of this research is to understand the high-level signals that these worms use to coordinate their regeneration, so that we can learn how to write our own signals. Someday, I hope that this could serve as the foundation for medical treatments for a variety of human ailments, including wound healing, organ damage, and age-associated loss of function.

My next milestone is to create an open-source protocol for replicating this experiment in a commercially available species. Currently, I have only observed the two-headed morphology in D. japonica, which is a planarian speices that I was only able to gain access to through my network in academia. To resolve this, I am now working to recreate the experimental protocol using D. dorotocephala, which are affordably available online and would make for a fantastic high-school science experiment!

At time of writing, I am running weekly iterations with this new species, searching for the proper concentration of gap junction inhibition required to replicate the two-headed morphology without fully stopping regeneration. In coming weeks, I also plan to explore other methods of controlling pattern memory using electric current and fields. I’ll be sharing updates in coming weeks/months, so keep an eye out!

Now if you’ll excuse me, the worms will have just finished their dinner and I need to go change their water. Again.